Vytorin

"Purchase on line vytorin, low cholesterol yogurt".

By: U. Roland, M.S., Ph.D.

Co-Director, Washington State University Elson S. Floyd College of Medicine

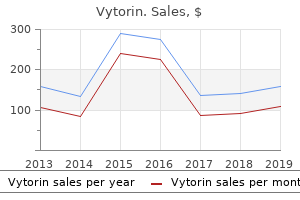

Much like the interpersonal relationship is the cholesterol in shrimp and lobster bad for you order generic vytorin from india, amenities are valued both in their own right and for their potential effect on the technical and interpersonal aspects of care cholesterol total vytorin 30mg visa. Amenities such as ample and convenient parking cholesterol biochemistry definition best purchase vytorin, good directional signs, comfortable waiting rooms, and tasty hospital food are all of direct value to patients. For exam- ple, in a setting that is comfortable and affords privacy and as a result puts the patient at ease, a good interpersonal relationship with the clinician is more easily established, leading to a potentially more complete patient his- tory and therefore a faster and more accurate diagnosis. Responsiveness to Patient Preferences Although taking into account the wishes and preferences of patients has long been recognized as important to achieving high quality of care, until recently this has not been singled out as a factor in its own right. Basic Concepts of Healthcare Quality 29 Efficiency Efficiency refers to how well resources are used in achieving a given result. Efficiency improves whenever the resources used to produce a given out- put are reduced. Although economists typically treat efficiency and qual- ity as separate concepts, it has been argued that separating the two in healthcare may not be easy or meaningful. Because inefficient care uses more resources than necessary, it is wasteful care, and care that involves waste is deficient—and therefore of lower quality—no matter how good it may be in other respects: Wasteful care is either directly harmful to health or is harmful by displacing more useful care (Donabedian 1988a). Cost Effectiveness the cost effectiveness of a given healthcare intervention is determined by how much benefit, typically measured in terms of improvements in health status, the intervention yields for a particular level of expenditure (Gold et al. In general, as the amounts spent on providing services for a par- ticular condition grow, diminishing returns set in; each unit of expendi- ture yields ever-smaller benefits, until a point is reached where no additional benefits accrue from adding more care (Donabedian, Wheeler, and Wyszewianski 1982). The idea that resources should be spent until no addi- tional benefits can be obtained has been termed the maximalist view of quality of care. In that view, resources should be expended as long as there is a positive benefit to be obtained, no matter how small it may be. An alternative to the maximalist view of quality is the optimalist view, which holds that spending ought to stop earlier, at the point where the added benefits are too small to be worth the added costs (Donabedian 1988a). The Different Definitions Although everyone values to some extent the attributes of quality just described, different groups tend to attach different levels of importance to individual attributes, leading to differences in how clinicians, patients, pay- ers, and society each define quality of care. Reference to current professional knowledge places the assessment of quality of care in the context of the state of the art in clinical care, which constantly changes. Clinicians want it recognized that, because medical knowledge advances rapidly, it is not fair to judge care provided in 2002 in terms of what has only been known since 2004. As a result, patients tend to defer to others on matters of technical quality. Patients therefore tend to form their opinions about quality of care based on their assessment of those aspects of care they are most readily able to evaluate: the interpersonal aspect of care and the ameni- ties of care (Cleary and McNeil 1988; Donabedian 1980). This often dismays clinicians, to whom this focus is a slight to the centrality of technical quality in the assessment of healthcare quality. Another aspect of care that has steadily grown in importance in how patients define quality of care is the extent to which their preferences are taken into account. Although not every patient will have definite prefer- ences in every clinical situation, patients increasingly value being consulted about their preferences, especially in situations in which different approaches to diagnosis and treatment involve potential tradeoffs, such as between the quality and quantity of life. Additionally, because payers typically manage a finite pool of resources, they often have to consider whether a potential outcome justifies the associated costs. Payers are therefore more likely to embrace an optimalist definition of care, which can put them at odds with individual physicians, who generally take the maximalist view of quality. Most physicians consider cost-effectiveness calculations as anti- thetical to providing high-quality care, believing instead that they are duty- bound to do everything possible to help their patients, including advocating for high-cost interventions even when such measures have a small, but pos- itive, probability of benefiting the patient (Donabedian 1988b). By contrast, third-party payers—especially governmental units that must make multiple tradeoffs when allocating resources—are more apt to take the view that spending large sums in instances where the odds of a positive result are small does not represent high quality of care, but rather a misuse of finite resources. In addition, however, society at large is often expected to focus on technical aspects of quality, which it is seen as better placed to safeguard than individuals are. Similarly, access to care fig- ures prominently in societal-level conceptions of quality inasmuch as soci- ety is seen as responsible for ensuring access to care, especially to disenfranchised groups. Although each definition clearly emphasizes different aspects of care, it is not to the complete exclusion of the other aspects (see Table 2. Only with respect to the cost-effectiveness aspect can it be said that the definitions directly conflict: cost effectiveness is often central to how pay- ers and society define quality of care, whereas physicians and patients typ- 32 the Healthcare Quality Book ically do not recognize cost effectiveness as a legitimate consideration in the definition of quality. But on all the other aspects of care no such clash is present; rather, the differences relate to how much weight each defini- tion places on a particular aspect of care.

Cassia lanceolata (Senna). Vytorin.

- What other names is Senna known by?

- Is Senna effective?

- Hemorrhoids, irritable bowel disease, losing weight, and other conditions.

- Constipation.

- What is Senna?

- Dosing considerations for Senna.

- Are there any interactions with medications?

- How does Senna work?

Source: http://www.rxlist.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=96642

Diseases

- Athabaskan brain stem dysgenesis

- Aortic arches defect

- Paraplegia-brachydactyly-cone shaped epiphysis

- Cardiomyopathy hearing loss type t RNA lysine gene mutation

- Ependymoblastoma

- Ankyloblepharon filiforme adnatum cleft palate

Plain English movement This is the idea that everyone cholesterol levels in quinoa generic 30mg vytorin mastercard, especially those who draw up our laws and run our bureaucracies keep cholesterol levels low cheap vytorin online, should write in a way that everyone can understand cholesterol levels slightly elevated cheap 20 mg vytorin mastercard. Groups have risen up in most of the English-speaking world to push for such reforms. In England the Plain English Campaign is one of them; for a fee it will put your text into plain English and award a crystal mark. Since most of us can communicate simply when we want to, it is not a matter of skill, but of culture and attitude. Political correctness All around us are examples of how language is being deliberately changed to meet political agendas. But, irrespective of whether we think some of the changes go too far, there is a valid reason for consciously trying to change the words we use. Language has a profound effect on how we view the world, and if we want social changes, then we must change the language being used. For writers the implications are clear: using inappropriate words may cause people to reject your arguments and (worse still) stop reading what you have written. But suppress any anxieties you might have about this during the actual writing stage. The time to take care of them is during the rewriting phase (see micro-editing). If you are working in a particularly sensitive field, ask someone who knows about the political nuances to go through what you have written – and advise if you have inadvertently given offence. Writers should give offence from time to time, but it should always be premeditated, not accidental. Political writing This is the ability to take a simple statement and make it so hard to understand that the reader becomes confused. Add some peripheral uninteresting information and avoid using one word when several will start to confuse things beautifully. Some bureaucrats have raised it to an art form, but it is not effective writing as discussed generally in this book. Politics of writing When we write we literally put our thoughts in black and white, thus making us an excellent target for anyone who wants to criticize. Not surprisingly, writing often becomes a battleground, where those who have power give a hard time to those who might wish to wrest power from them in the future. Modern word processing packages allow us to use a wide range of them nowadays, but this does not mean that you have to use all of them at the same time (see typefaces). Pomposity A disease of the over-comfortable, characterized by a tendency to use long words and needless phrases. Pompous initial capitals There is great confusion over the use of capitals. Some people feel that an Initial Capital Letter conveys Dignity, and should therefore be used to describe People and Institutions whom we know and value. Thus we talk about Professors and University and Gynaecology and Resource Management Initiatives. Also, most research on writing shows clearly that capitals are hard to read and slow the reader down. They send a strong message that We are Important (though you, dear reader, are not). And when we start writing Consultants and Doctors but patients and nurses, then it risks becoming offensive – and therefore bad communication. Make an exception to this rule wherever there is likely to be major confusion. Positives Readers find it easier to cope with what is rather than what is not. This has demotivated several otherwise good writers (see macro-editing). Posters A poster is simply a way of communicating informa- tion on a single sheet of paper, cardboard, etc. We are surrounded by them, which suggests that they are an excellent way of putting messages across (see PIANO). The medical and scientific community has adopted them as an important part of their intraprofessional communication. But in this context the posters are usually dull and 97 THE A–Z OF MEDICAL WRITING badly presented, apparently favouring cut-down versions of the scientific paper (see IMRAD), rather than using the medium to its full potential.